| |

|

|

FACE TO FACE

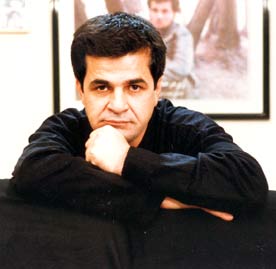

An interview with Jafar Panahi on the occasion of

the screening of his latest movie, Offside

Reporting To History

Massoud Mehrabi

Jafar Panahi, born in 1960 in the ethnic Azeri-populated town of Mianeh in northwestern Iran, rose to international fame as his first feature film, The White Balloon (1995) claimed many awards at international film festivals. His second movie, The Mirror (1997) was not as successful; but he managed to regain his internatonal profile with The Circle (2000) and The Crimson Gold (2003). His latest movie, Offside (2006) shared the Berlin Film Festival's golden bear with another film, The Soap. In Offside, Panahi discusses the ban on entry of female spectators to Iranian stadiums. In this film he depicts the story of a group of girls who dress as boys in order to find their way into the stadium where Iran's national football team is taking part in a World Cup qualifying match.

Where does your interest in cinema come from? Where does your interest in cinema come from?

Jafar Panahi: Many years ago, when I was 12 years old, I wrote a story which won a prize at our local library. At that time, amateur filmmakers made 8mm films at the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Youg Adults. They offered me a part in a film named The Fat One and the Slim One. This was my first step in cinema. The story was about children’s game in which the loser should carry the winner on his back. It was easy when I had to carry the slim boy but the problem started when I had to ride. Then he had to find a solution which turned out to be giving me a ride in a wheelbarrow. The film was about five to six minutes long. Then I worked on a number of films as assistant director. My dad, who painted homes for a living, was the first to encourage me. Later I bought a photo camera. I used to take photos and put them on display at exhibitions. Then I continued taking photos when I was drafted during the war with Iraq. I held a photo exhibition at the barrack. It was in Marivan (a city in Iran’s Kordestan) when a local TV official liked the photos and offered me a job. They wanted war reports to be broadcast on the radio. I did not like this. Instead, I offered to produce reports on film. They finaly accepted it and sent me to the TV station.

And you started working with those old 16mm cameras that had three lenses for close-ups, long shots as well as a wide-angle views.

That is right. They had a lab and I developed the films quickly and they could see what I had shot. Those documentary reports were usually shown on the local TV in Kordestan. Later, I happened to be filming my former comrades in action. They had their weapons and I held my camera. I filmed a report about an operation codenamed "Mohammad, the Prophet of Allah" and I did the editing too. That 23-minute film was aired on the national TV.

Did you learn film editing there and then?

I started editing when I used to make 8mm films. I was so keen to learn and a friend at the Kurdistan province TV helped me a great deal. I completed my military service working with the local TV. Then I passed the university entry examination.

To what faculty were you admitted? To what faculty were you admitted?

I was admitted to the University of Radio and TV, an academic center that trains the students for working with the Iranian radio and television. There were some sixty of us who later specialized in various areas such as directing and screenplay writing. When Kambuzia Partovi was making his film, The Fish, I worked as his assistant director. When Golnar was being edited, I made a 16mm documentary about the puppets used in Partovi's film as my college project. It was named The Second View.

Szabo’s film.

What did you do after the college?

I worked at the local TV station in Bandar Abbas in southern Iran where I made four or five films. Some of them including The Friend and The Last Exam won several awards at the 1st Iranian TV Festival. At that time, I was Abbas Kiarostami's assistant when he was directing Under the Olive Trees.

And it hapend so casually, didn't it?

One day I called Kiarostami and left a message for him. I told him who I was and what I was doing and that I was interested in his films and liked to work with him. I was lucky and he still needed people for his crew. It went so smoothly. I went on location and introduced myself. After two or three days of working with him, I became his first assistant.

What did you learn from Abbas Kiarostami? Was it his view of the cinema or you liked the technical aspects of working with him or the way he made his films?

I had experienced working as assistant diector with Partovi. I liked the way he worked with his actors. But it was different in Kiarostami's cinema. He used to look for what he wanted; so he did not need much of a performance. The significant characteristic of his work was his obsession with images. This was not something you would always see. In his cinema, although the pictures were based on a screenplay, he had his own expression. I paid attention to the way he took care of every detail. Later, when I started to make my own films, I treated actors and acting in another way but I knew that his view had influenced me. Now I might even enact the part for my actors and tell them what I want; but I would definitely look for the most physically appropriate actors in the first place. he worked with his actors. But it was different in Kiarostami's cinema. He used to look for what he wanted; so he did not need much of a performance. The significant characteristic of his work was his obsession with images. This was not something you would always see. In his cinema, although the pictures were based on a screenplay, he had his own expression. I paid attention to the way he took care of every detail. Later, when I started to make my own films, I treated actors and acting in another way but I knew that his view had influenced me. Now I might even enact the part for my actors and tell them what I want; but I would definitely look for the most physically appropriate actors in the first place.

And this is what Kiarostami does. He does not start his work before spotting the appropriate actors.

Not absolutely… What impressed me in Kiarostami's work was the importance he attaches to images. I learned that images are more important than the screenplay. It is so important that sometimes it is the image that talks and forms the screenplay. In my experience with Partovi, one day I noticed that the actors and the camera were ready but he wouldn't tell the cameraman about where he is to be positioned. When I asked why, he said: "That is all right. I have a story with two kids. Camera positon really does not matter." That was how Partovi saw things then. But Kiarostami was not like that. When he wanted to show me a location for the first time, he made blindfolded me one kilometer before reaching the place. When we were there, he opened my eyes and I saw the location of the finale of Under the Olive Trees. This beautiful shot was not easy to come by. I was sure that Kiarostami had visited many places for that. The camera has its designated place. And that is where a cinema character creates his real role.

Your first film, The White Balloon, is still lingering in the minds of Iranian and non-Iranian viewers after so many years. It brings to mind the name Jafar Panahi. It is indebted to Kiarostami's cinema in those years. How did it take shape? The screenplay belongs to Kiarostami, but still one could see traces of your independent cinematic character in that film.

When I was studying at the college, I used to work at the film archive. So I had an opportunity to watch many films. I was a Hitchcock fan and watched all of his films and knew their bits and bolts. This was when I had already made those short films in Bandar Abbas. Yes, the screenplay belonged to Kiarostami but the film was something different. I believe, that is because of the rhythm and the editing which I had learned from Hitchcock and the Italian neo-realist movies. I tried to work with what I had learned. And I had my own way of directing. All the time I was thinking that my teachers were waiting to see this film. In the back of my mind I was preparing for an exam.

Even you could not foresee the international success of The White Balloon. What did bring about such a success and made the film so enduring?

I have never tried to find out why it did happen. However, after that film, cinema was the most important thing in my life. I wanted to continue properly what I had started. I know that it is hard to become successful. But continuing the success is even more difficult. I needed to think of a new way. Sticking to one style could land me in repetition. I was looking for a fresh narrative and The Mirror was the outcome of this way of thinking. cinema was the most important thing in my life. I wanted to continue properly what I had started. I know that it is hard to become successful. But continuing the success is even more difficult. I needed to think of a new way. Sticking to one style could land me in repetition. I was looking for a fresh narrative and The Mirror was the outcome of this way of thinking.

But The Mirror was not as successful as The White Balloon.

Maybe because The Mirror was a bridge between The White Balloon and The Circle.

We shall get to The Circle later. But why The Mirror was not as successful as The White Balloon although it moved along the same line?

It is always like that. Many of the world's filmmakers who have had a great first film failed to repeat their success. In The Mirror I was looking for a new look. At the middle of the movie everything begins to change at once and we see a new form. It could have been more pleasant if I followed along the lines of the first half of the film. I thought then that I was living in a society of split characters. When at work, everybody was pretending to be someone they were not at home.

So it was that realization that changed The Mirror from halfway through the end?

I tried to bring something from the content to the form and this caused a split. One piece was what we were making and another piece was a reality the protagonist was giving shape to. Of course, we are making both of these pieces, but I wanted to say that these split characters are living in the same society. It could look crude now, but it was an experiment. Perhaps that pure look did not exist in The Mirror and it failed to repeat The White Balloon's success. In The White Balloon I told the story in a classic way but in The Mirror I broke the barriers and started to experiment. But if I did not make The Mirror, I could not reach The Circle in which I used the form at the service of the content. I set aside the classic principles and what I had learned from those Hitchcock movies and other films. Now, I wanted to show that I was interested in something else. In the credits of The White Balloon and The Mirror I did not use the phrase "A film by Jafar Panahi"; because I thought I still had not made my first movie. Those films were my drafts and practices which were to take me to my ideal movie. "A film by Jafar Panahi" started with The Circle. My first film is The Circle.

After The Circle you moved towards a semi-journalistic cinema which has nothing to do with causes and only deals with effects. How did you move from the delicate and enduring story of The White Balloon to these radical statement-like subjects?

When you are making films for or about children, the sheer presence of children lends a delicateness to the film. When you are looking at the world from the point of view of a child everything becomes softened even if you are dealing with social issues. And you will not see the violence that exists in the adults’ world. On the other hand, I have always been interested in social issues. One reason for this could be that I have always lived in neighborhoods where the people were not well off. Their problems touched me. The world that I knew has left its mark on my last three films. And I have always thought that I was responsible to report to history. I am responsible to report about where I have lived and on the conditions of life. This interest in reporting to history dates back to my student days. At that time I made a film named Ritual Poniarding. In the credits of that film I wrote: "Dedicated to History". I wanted to present a document to those who would watch it in 20 or 30 years time. The film provides a sample of what was going on then. Maybe that is where the journalistic look comes from. This reporting to history is evident in The Circle, The Crimson Gold and Offside. They speak about social problems and limitations. And it was The Circle that paved the way for all this; first reporting to history and second; a different view on the artistic form.

The Crimson Gold is in one way a continuation of The Circle. It addresses poverty and prostitution and a reflection of a society that abuses women. In The Crimson Gold there are class divide and the contradiction between poverty and wealth; something which gives rise to class divide in every society. How did this way of looking at things continue? addresses poverty and prostitution and a reflection of a society that abuses women. In The Crimson Gold there are class divide and the contradiction between poverty and wealth; something which gives rise to class divide in every society. How did this way of looking at things continue?

Well, after The Circle, my thinking became more clear-cut. Now I had to make films about limitations which could be about just anything, including the problems of women and class differences. All of this could be a starting point for a movie. You mentioned women and prostitution when you talked about The Circle. But all of this could have financial roots. My report to history could include any one of these problems. That is particularly because we are living in a society where economic moves do not follow a natural course. Due to considerable growth of the affluent and poor strata, the middle class is being phased out. These are people who have not become rich in a natural way. They cannot create jobs with their wealth. This adversely affects the situation of lower strata and widens the class gap and causes corruption. That is the same all over the world. But in other places social classes have a natural form and there is an interaction between various classes and they live together in spite of their differences. But in the post-revolution Iran, a wealthy class has emerged. They have not become rich in a proper way and have created corruption which is manifested in prostitution and other problems. The lower strata are being victimized. Hossein, the protagonist in The Crimson Gold, is one of these people. He is gradually vanishing without anybody noticing.

By the term "journalistic," I mean in these films we are dealing with appearances. As an Iranian, I know what you are saying but for the next generation and for those who are not living in Iran, the causes are not clear. In both The Circle and The Crimson Gold we are watching an outer layer and do not see the underlying causes of the situation.

I believed explaining them would be irrelevant.

I am not calling for an explanation. I am talking about semiotics. Signs that could familiarize us with the rootcauses at least in a symbolic manner.

We see these signs in many different forms. When the man living in the high rise tower explains how his father had built it and explains how he makes his own living, this makes a lot of things clear. Any explanation more than that would be redundant. If I wanted to explain individual characters in The Circle, it would have blocked the viewers' thought current. This kind of film should only give a clue to the viewer to begin to think. In the film, we see a form of society. I am not sure whether it is part of my responsibility to explain the roots. I do not believe that a film should solve the problem. The signs you are talking about are here and there in the movie. But I have not deliberately laid any stress on them in order to allow the viewer make his mind about the problem. rise tower explains how his father had built it and explains how he makes his own living, this makes a lot of things clear. Any explanation more than that would be redundant. If I wanted to explain individual characters in The Circle, it would have blocked the viewers' thought current. This kind of film should only give a clue to the viewer to begin to think. In the film, we see a form of society. I am not sure whether it is part of my responsibility to explain the roots. I do not believe that a film should solve the problem. The signs you are talking about are here and there in the movie. But I have not deliberately laid any stress on them in order to allow the viewer make his mind about the problem.

In Offside we are facing a motif different from those of The Circle and The Crimson Gold. It is now a special problem concerning the women in the society. How did you come up with this idea? What was your motivation? Was it just the fact that women are not allowed to enter football stadiums? Or you wanted to show a bigger problem?

In Offside we are still facing the problem of limitation. Problems that exist for a certain gender that cannot move along the other gender. This was the foundation of my work. On the other hand, as a football fan I was aware of the problem. Once when Iran's national football team was coming back from the World Cup and they were to be welcomd at Azadi Stadium, I went there with my wife, my son and my daughter. When we reached there, they no longer allowed anyone to enter the stadium. It was there when I heard that some five housand women had opened their way into the stadium and the officials barred other women from entry after that. This image lingered in the back of my mind. A couple of times I went to watch a match with my daughter who is a football fan. And everytime, I had to ask my wife to come with us so that my daughter could return with her if she was not allowed to enter the stadium. They did not allow her. I don’t know how she made it, but she was with me after ten minutes. This was yet another fillip. The last one was the World Cup qualifying match in which Iran nearly found its way into World Cup 2006. Then I thought it was time to make this film.

In your previous films you were in control while you were filming. But in Offside you had to work in an improvisational way. Did you have any plan beforehand how to shoot the events that take place only once?

The experience of working with the TV as well as filming in the battlefields helped me cope with this problem. And of course I had my plans. I knew what I wanted for various parts of the film. And as I am well versed in editing, my mind worked in a parallel way and I knew which shot was to be placed next to what. Sometimes things went ahead the way we wanted them to go. Sometimes this was not the case. If this happened, we furthered the scene with a new mise en scene. I knew how would every scene end but I had no idea about how the whole film would end. While the game was going on, I was sitting in the stadium with director of photography Mahmoud Kalari, but there was a second unit downtown. We were thinking of what would have happened if Iran lost the match. Then the ending of the story could change. But with the result of the match for Iran, it was as though we had written the screenplay for the match.

In fact, before the filming, you had only written half of the screenplay; not all of that. screenplay; not all of that.

We had a screenplay that changed day by day. Every session of the filming went ahead based on what had happened in the previous session. For instance the scene about touring the city on a minibus was added to the film later.

In The Circle and The Crimson Gold, you have chosen the actors in a way that they had their equivalents in the society. How did you select the girls who perform in Offside?

Just imagine that they are girls disguised as boys in order to watch a match. They are different with the characters of my previous films. In my previous films, characters directly play their own social role with all of their problems. In Offside, the girls want to achieve their goal by pretending to be someone else. However, they belong to a social class and have their equivalents. We would easily identify them in the society; football fans, cowards, students, and so on.

By making Offside, did you mean to solve a social problem?

My first aim was presenting a report to history. That is what I have done in my previous films too. And then I was looking for a solution. At the same time, I suffered to find out that we were so apart from each other. In the movie, I show that people are gradually getting closer to each other. At the end, they take part in a national celebration thanks to their love for their homeland. This is where we see them together. Now, if we return to the world outside the film, we see that we have fallen apart from each other and that we need a motivation to get closer to each other. At the end of the movie it was inevitable that everybody would come together. At the bottom of my heart I hope that this film could pave the way for women to watch football at the stadium. I have been gathering women's organizations around this film and I am trying to insist on the public screening of this film. All that is because I think, maybe for the first time, we would be able to solve a problem with a film.

Half of the girls we see in Offside are not real social types of the Iranian society. There is particularly one macho type who speaks in a hoodlums-like way. I believe Iranian viewers would repel her. Characters like this are not allowed to enter stadiums even in the UK. Couldn't you cast another character that would be closer to the image of an Iranian woman? Although I admit that this character is interesting enough for a film. Iranian society. There is particularly one macho type who speaks in a hoodlums-like way. I believe Iranian viewers would repel her. Characters like this are not allowed to enter stadiums even in the UK. Couldn't you cast another character that would be closer to the image of an Iranian woman? Although I admit that this character is interesting enough for a film.

First of all we need to consider that 90 per cent of those who go to watch football are young people, starting from the 12-year-olds and ranging to the middle-aged people who have been football fans since their adolescence. The second point to consider is that all over the world a certain type of people go to watch football. They speak and behave differently when they are at the stadium. Particularly in all-male stadiums of post-revolution Iran, men can say whatever they like. I have heard them talk rudely and I would have been embarrassed before my son if he was with me. The characters in this film have been chosen out of the same people. You could have questioned why they are not representd in the film if that was the case. That girl comes from the same background. And she has made herself look like them, so that, she would look normal. And in fact, few people find her a stranger in that setting. Even the soldiers could hardly tell her gender. Another thing to consider is that we are not supposed to have representatives from all the women in the society in a film about women. Those who go to the stadium are interested in football. These girls have tried to look like them. I believe we made the right choice. I could get much closer to reality; but I decided to intervene a little bit. In reality, you could hardly tell the girls in the crowd. I intervened in the sense that I pictured more cultured football fans. For instance, in the lavatory scene, the boys help that girl to escape. I wanted to say that male spectators are cultured enough to tolerate female spectators next to them.

How do you think Iranian families would react to such a girl when they finally see your film? Would they identify with her?

Yes. I saw this at Fajr Film Festival. I visited movie theaters in nearly ten sessions that this film was screened during the festival. This included the theater which was dedicated to media people as well as the ones frequented by ordinary people. The reactions were unique. I could see that they identified with that character. Iranian viewers responded very well. One day after the first screening, distributors called to discuss screening contracts.

In this film, and also in The Crimson Gold and The Circle, you talk about abnormalities which create problems on the way of your films' public screening in Iran. Some would say you do this deliberately.

We know where we are living and what kind of problems we might come across. I always have a strong motivation and if I keep thinking of these problems, then I would be imposing a censorship upon myself. This will make the film vulnerable. If I make a film against my own will, then that will be no longer my film and I would have lied to myself. No, I do not think about these problems. My most important problem is to make the film. That is difficult enough. I got the production permit for this film with another name and started filming without anyone noticing. Had I thought about the problems I would have not started making the film in the first place. The next stage is to cope with the way my films are screened. I insist on my idea and do not cut anything out of the movie and the film does not get a screening permit and finally finds its audience on a DVD or VCD version. Do you know anybody who has not seen The Circle in Iran? And now there is Offside.

At the end of the day, do you make your films for Iranian audience or what? or what?

make them for myself.

How important is the mainstream Iranian cinema and the screening of your films to you?

Well, it depends on a couple of things. Befoe making the film, no one, even the audience, is important, and I do not attach significance to screening, critical reviews or festivals at this stage. What is important is that I want to make a film based on my knowledge and experiences. The stress starts after the film is made. It is then that I ask myself: What if the film is not seen? Then what is it good for? I would ask whether one can make a film which may not be seen improperly or which may be missed by Iranian viewers? If there is no financial profit in this film, then how am I going to make my next movie? In the first stage, I evade self-censorship by not thinking about the problem. I am now used to this, so there is no problem. So far I have made four movies and I am proud of them. Offside is the fifth one. I console myself by saying that I have made the films I wanted to make.

Is that why you edit your own films? Are you then reasoning that you are making the film for yourself?

I don't know. I wanted The White Balloon to be edited by someone else. I have been interested in editing since I made 8mm films. I even used to edit my friends' films. When I made The White Balloon, everthing was prepared for someone else to edit the movie. But when he saw it, he made a comment that disappointed me. After that, I did not give my films to anyone else for editing so that no one could impose his taste on me.

There are some long minutes between the minutes 60 and 80 of Offside. The rhythm could be improved if someone else edited it.

Unlike my previous films which started with a shock, I started Offside with a smooth rhythm and then took the audience up with me gradually. I do not think that parts of the film are boring. I have included small details that prevent boredom. I have made it a 90-minute-long film based on the timing of a football match.

Are you producer of your films in order to prevent others from imposing their views on you? imposing their views on you?

Yes. Because of problems that exist in Iran, working with another producer could be problematic. I can resist if I am told to cut part of the film. Another producer might see this as a hindrance to the production of his next films. Then I would have a guilty conscience for financial loss that I have inflicted on him. But there is no such problem if I produce my own films.

What do you think about the mainstream Iranian cinema?

All sorts of films should be made in every country. They supplement each other. A market-oriented mainstream cinema can assimilate the audience and run the film industry. On the other hand, art films could improve the quality. They supplement each other. We have all sorts of films and have to see what kind of films our audiences like to see. This is a way of respecting the audience. I believe Offside could be included in both of those categories. It could satisfy ordinary viewers as well as the elite.

You are one of those Iranian filmmakers who have been accused of making films for festivals. It means you make your films in a way that deprives the Iranian viewers of seeing them.

They could describe any move you make in a certain way. And they also create problems for your success. When The White Balloon became successful, somebody asked me how much was the prize worth? I said sixty thousand dollars. He said: Now you have sixty thousand enemies. When I was making The Mirror, I saw a film critic who told me: "No matter what you are going to make, I have already written the review!" When you are famous everybody sees you. I am pointing out social problems and I know that I would come across troubles. The first ones to put labels on you are the politicians. And they pretend that they are saying what the people say. create problems for your success. When The White Balloon became successful, somebody asked me how much was the prize worth? I said sixty thousand dollars. He said: Now you have sixty thousand enemies. When I was making The Mirror, I saw a film critic who told me: "No matter what you are going to make, I have already written the review!" When you are famous everybody sees you. I am pointing out social problems and I know that I would come across troubles. The first ones to put labels on you are the politicians. And they pretend that they are saying what the people say.

The type of films you make belongs to alternative cinema which does not have a broad audience. As producer, how preoccupied you are with distribution, boxoffice return and making your next film?

I make a film once in every three years. That is although I can make two films a year and even films that could sell inside Iran, my first preoccupation is whether I like this movie. If the answer is yes, I would give all my life to make it. Now I am well-known outside Iran. Naturally there are people abroad who may like to work with me. What I do is that I start a film and halfway through the production I find a partner. This is how I fund my films. So far I have not made any loss. I am not worried about having a producer. I was offered a blank check when I started to make Offside.

That is fair enough to say that you make your films for yourself. But your audiences have been mainly foreigners.

This has taken place against my will.

Hasn't this given a non-Iranian look to your subsequent films? Haven't you been after pleasing non-Iranian audience when you were making Offside? Haven't you been after pleasing non-Iranian audience when you were making Offside?

If it were only for the sake of festivals, Offside should have been never made. Offside has a wider range of audience. But since it has taken shape along a documentary line, it has limited me in a way.

However, foreign audience and their taste affect your work. This is undeniable.

I cannot answer that precisely. One may be unconsciously affected by praises. But my love for cinema is stronger than that. For example, when The White Balloon was being screened, Kiarostami was asked to write something about me. He wrote: "Thanks to Panahi's love for cinema and his thorough knowledge of images, it is unlikely that he will ever make a poor movie." I truly love cinema. It is my world. I have achieved anything I wanted. I have been at the podium of every film festival and won many awards. And I am honest to myself. If I were overwhelmed by praises, I should have continued making more films like The White Balloon. But I realized that I needed some fresh experiences. That is why I have tried to be different with every new film. After I make a film, my first thought is whether it is going to be screened in my own country. My greatest pleasure was in this year when I saw that Offside was screened at Fajr Film Festival.

What is your next plan?

I really do not know what will come up. When I finishd The Circle, I thought I was not going to make any other film. I had the same feeling when The Crimson Gold was finished. Three years must pass. I have several plans. For instance there is a historical plot about Hassan Sabbah which takes place a thousand years ago. I like to make it. But I am still not sure that this is going to be my sixth film. I should wait until I really feel like making it.

Will you work with professional actors in your next films?

Maybe. It depends on the subject and the nature of the film.

Good luck!

Thank you.

|

|

|

2 permalink |

|

|

| |

|

|

Friends' Articles

Friends' Articles

|